I’ve had several people ask me how my interest in production and rhetoric connect. For me, it is obvious. I view production as a creative and technical skill that I love learning more about. With rhetoric, I enjoy debating the why’s and how’s in life and also believe it is my duty to explore experiences outside of my own before putting content out into the world. As much as I love journalism and media, it has a bad reputation for excluding marginalized identities and experiences. I don’t want to make the same mistake.

It’s not a perfect science, but I think it’s really important. My studies are something I not only take seriously but something I have a lot of fun with as well. Including binging existential films! I am currently taking a course taught by Leah Kalmanson called Existential Films. Here are some of the films I’ve enjoyed so far!

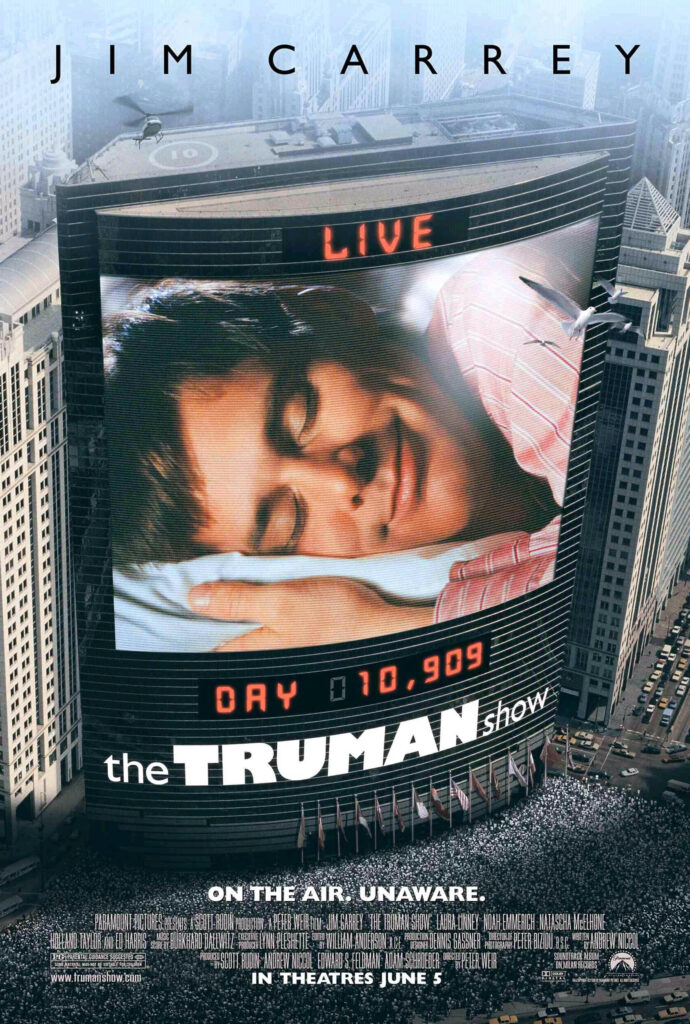

The Truman Show (1998)

The Truman Show is a commentary on how we invest in “reality” tv and if we are living in a simulation. The film follows Truman in a world where he is supposed to believe he is living a successful and normal life. But in reality, Truman lives on a fake island in the middle of Hollywood in a giant dome where everyone is in on a big secret, except him.

Truman is the single unknowing subject of a live broadcast that follows his every move, captured by hidden cameras. Every person in his life is a hired actor and everything he does is heavily influenced by the executive producer, Christof. Manipulating Truman since he was born, Christof dedicated his work to convincing Truman why he needs to stay on the island. As he begins to see some cracks in the illusion presented to him, he gets a strong urge to leave the island.

After multiple attempts trying to leave, the main characters in his life begin to crack. Christof begins to make a few desperate attempts to keep Truman in the narrative. One of these attempts including pretending to reunite him with his believed-to-be-dead father. This appears to be Truman’s breaking point and makes he his escape in the middle of the night. Finally, Truman reached the edge of his world and realizes exactly what his life has been. And he decides to leave it all behind.

The Truman Show addresses questions of what powers dictate our state of being and if we are living in a simulation, does that really change anything? Christof clearly plays the perceived role of God, as he has the ultimate power over this world he created. It’s up to Truman to see the control he is under for what it is. He is the only one who can advocate for himself, as everyone else is reaping the financial benefits of broadcasting his life.

The movie plays on this idea of does the prisoner know he’s imprisoned if he knows no other way of living. Christof seems to believe that if you make the cell nice enough, that he’ll prefer to stay in it. But even in a “perfect world,” one begins to itch to live in some form of perceived freedom when they feel too heavily controlled. The film creates the question of “what would you choose?” If you knew you were in a simulation created for you, would you stay in it? Or would you leave to a life of uncertainty that could possibly lead you to freedom?

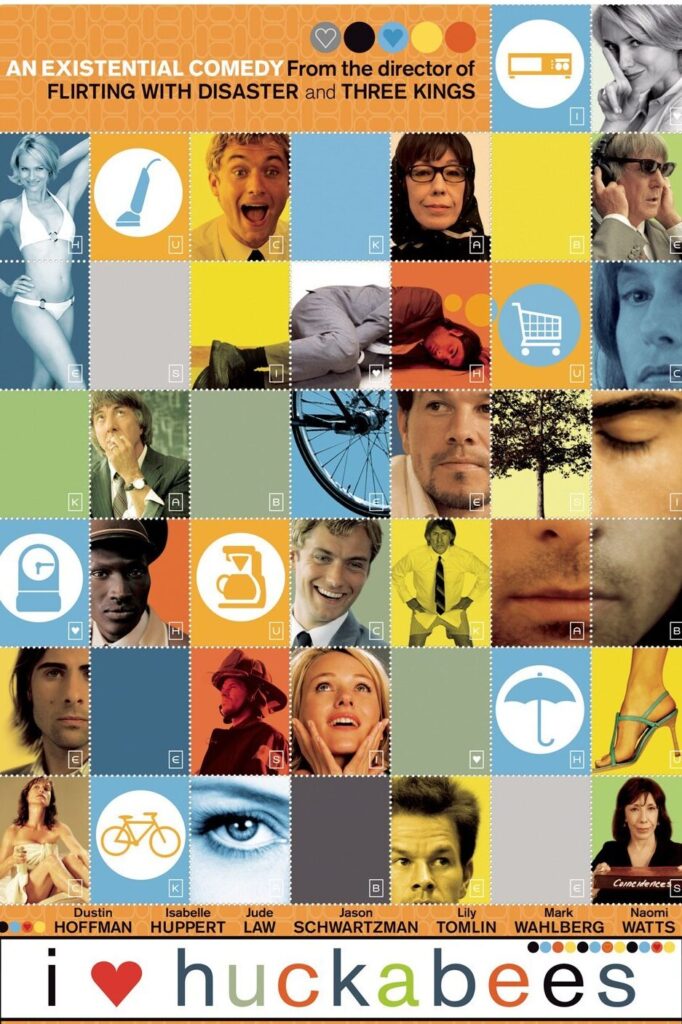

I Heart Huckabees (2004)

I Heart Huckabees follows Albert in his questioning and arguable discovery of the meaning of life. The existential detectives, which Albert meets by “coincidence,” use the term universal interconnectivity to describe how we are all connected and everything matters. Later, we meet “the french nihilist” that proposes Tommy and Albert enter a non-thinking state of “pure being,” to avoid daily human drama. She believes everything we do is meaningless and has no connection. In the end, Albert concludes that everything really is inextricably connected, but necessary to arise from inevitable human suffering.

The movie intentionally or unintentionally points out the humanistic extremism of life’s most challenging questions. It’s very human of us to think of the answers to existential and even everyday questions as all or nothing. This way of thinking causes such disappointment for us that actually reaching said extremes hardly happen. Like a strict diet, we yoyo throughout our lives trying to attain the unattainable that we are often left disappointed.

As the movie wraps up, I found Albert, the French Nihilist, and the existential detectives’ theories to be a gross oversimplification of a timeless philosophical debate. It felt a little rushed and taken over by Hollywood’s interpretation of meaning for my liking, but it was entertaining, which I believe to be their main goal.

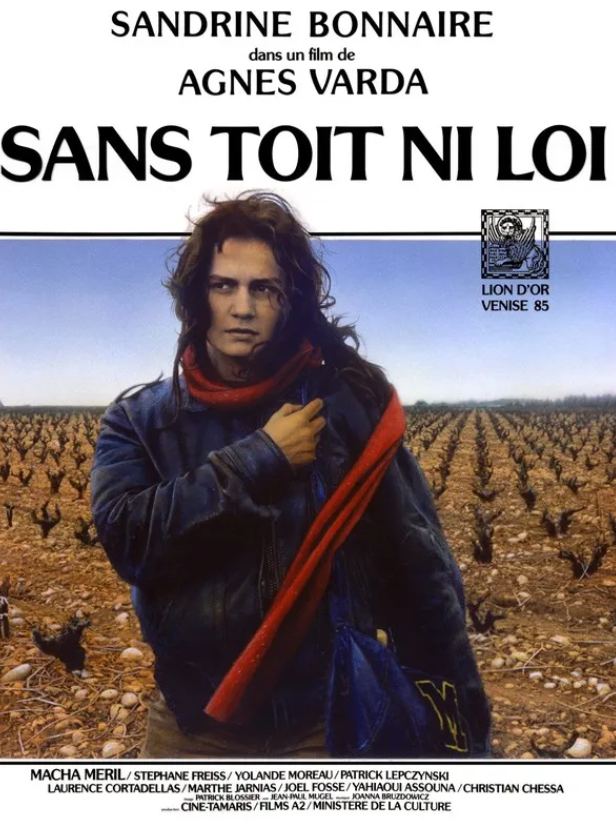

Vagabond (1985)

The french film opens with Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire) frozen in a ditch. The movie then flashes back to the beginning of when those interviewed can recall her existence. This pseudo-documentary or “mockumentary” style film shows Mona’s travels across the French countryside during the previous weeks. Rejecting societal norms, Mona is independent to the point where she prioritizes freedom over comfort.

Time and time again, Mona turns down opportunities to return to society and live comfortably by maintaining a job and earning her keep. Instead of accepting or pursuing any offer made to her by those she encounters, Mona’s desire to be free wins each time. Instead, she chooses to live by the will of whoever will put her up for the night or feed her. Some envy her and some despise her way of living, but in the end, it’s her pursuit of freedom that leaves her hungry, exhausted, and leads her to her cold and lonely death.

The film shows that Mona is both more than just a dead body in a ditch while simultaneously being nothing more than a stranger. This contradiction fuels the popular existential question of “do we matter?” Exploring themes developed by Simone de Beauvoir and critiques by Steven Cahn, the film critiques true freedom and meaningfulness. Similar to what Mona believes she was doing, Simone de Beauvoir believes that absolute freedom comes from individual spontaneity and not from an external institution, authority, or person.

Mona truly believes that the way she lives has abandoned all societal ties, but in all actuality, she still has needs of the flesh that need to be fulfilled. Relying on strangers to provide her with the essentials is still relying on human decency, and that in itself is still being enslaved to the rules of society.

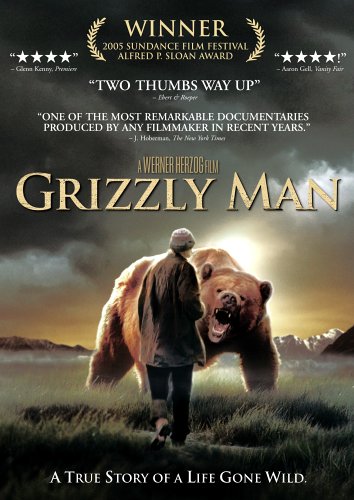

Grizzly Man (2005)

Grizzly Man, a film created by German director Werner Herzog, follows the story of Timothy Treadwell’s final years living among wild grizzly bears on an Alaskan reserve. Claiming to be their protector, Treadwell was a self-proclaimed conservationist who believed he could bridge the gap between human and bear. Documenting his time in the wilderness, Treadwell caught almost every moment on camera, including his and his girlfriend’s tragic death by a bear attack in 2005.

The film actively includes critique and support for Treadwell’s decision to live among the grizzly bears for 13 summers. It highlights the fact that Treadwell’s background does lead us to believe that he may have had some form of mental illness or long-term effects from his drug and alcohol use that may have contributed to his unique mind.

The film leaves the audience with mixed emotions about Treadwell’s morals and ethics when it comes to the grizzly bears. Some would argue his “protection” really led to the harmful conditioning that led the grizzly bears to feel safe in the presence of humans, even hunters.

Political philosopher, Jane Bennett, acknowledges that even the human body is but material. It’s easy to question Treadwell on several fronts, but it is undeniable that he was aware of this concept. Several times throughout the documentary, he believed that the longevity of the grizzly bears depended on human sacrifice, even if it meant his own. And he was perfectly okay with that. As Bennett states “any action is always a trans-action,” (101) and in the end, it seems that Treadwell’s 13 summers living among the grizzly bears in Alaska was paid in full with his life.

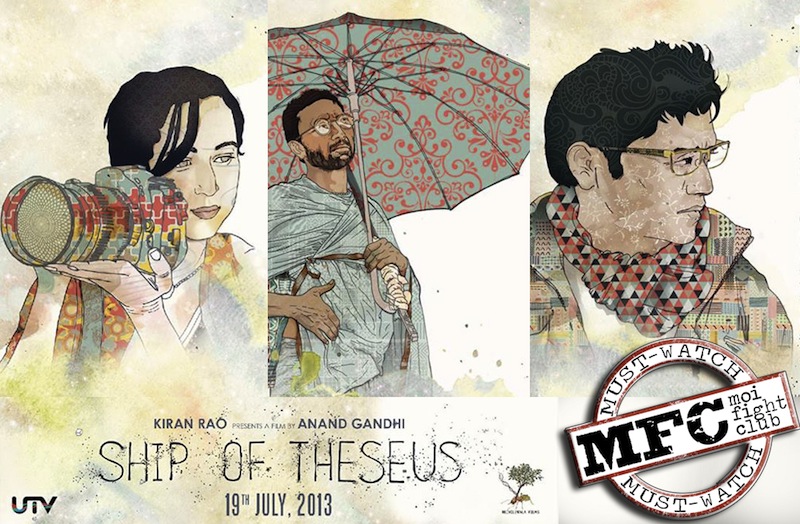

Ship of Theseus (2012)

Ship of Theseus is a film written and directed by Anand Gandhi that explores existential questions of “identity, justice, beauty, meaning, and death” through the tales of a photographer, a monk, and a stockbroker. This film is a story that plays out the riddle of the Ship of Theseus, as the title insinuates. We see how each character’s identity is tested and changed with the organ replacements they received. We often view our personality with our mental values and experiences, but this movie encourages us to see how our physical ailments or abilities contribute to what makes us who we are.

The film opens by introducing us to a photographer who lost her eyesight due to a cornea infection. We follow her frustration and struggle with photography, both before and after her eye transplant. After her eye transplant, she loses her “eye” for photography. Seeking new inspiration at a beautiful destination, the next step in her photography journey is left a mystery.

Next, we meet a Jainist monk who is battling a failing liver but has vowed not to use medication or get an organ transplant due to his dedication to not harming any organism. In the end, he decides it’s not his time to go and the film alludes to him seeking a new liver.

Last, we are introduced to a stockbroker who, after having undergone a kidney transplant of his own, seeks justice for a man whose kidney was stolen while undergoing appendix surgery. After finding the recipient of the kidney, he tells the man he needs to make the situation right and pay for a new surgery. In the end, the man who had his kidney stolen decided to keep the cash sent to him by the recipient, and the outcome is left a mystery.

In the last scene of the film, we see all of the characters who received organs viewing a short film that represents the Allegory of the Cave, or Plato’s Cave. The clip shows a shadow of the man in the walls of the cave he is exploring and in the end, he did not make it out of the allegorical prison/cave described by Plato.